How Do a Liberal Arts Help a Psychology Degree

Well-nigh students who take the general, introductory psychology course (hereafter called Psychology 101) are not psychology majors. They take the course because they think information technology will be interesting, or considering they come across connections between psychology and their major field of study, or because it satisfies a curriculum requirement. My argument here is that nosotros should think of Psychology 101 not every bit technical grooming for majors, but as an extraordinarily valuable liberal arts grade for all. When we teach the class from a broad liberal arts perspective, we serve the real needs of the many non-majors as well every bit those of the majors. Psychology is today, in many ways, the core discipline in the liberal arts; it is what philosophy was 100 years ago. And Psychology 101, different more advanced psychology courses, presents an integrated view of the whole subject area.

More specifically, I volition contend in this essay that Psychology 101 is potentially the almost valuable liberal arts grade a pupil tin can take, considering it, more than than whatever other course (or certainly more than virtually other courses):

1. makes meaningful connections to other disciplines,

2. brings students upwards to date on archetype philosophical questions,

iii. provides frameworks for understanding oneself and making life decisions, and

4. promotes disquisitional thinking.

The "teaching tips" in this essay all have to do with ways of achieving these four liberal arts goals in the classroom.

Psychology 101 Makes Meaningful Connections to Other Disciplines

No matter what a educatee is majoring in, he or she is probable to notice meaningful connections between that field and psychology. I like to illustrate this indicate on the first day of class with the post-obit sit-in:

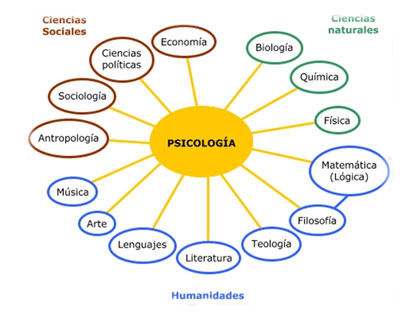

Figure i. The Psychocentric theory of the academy. Each connection between psychology and some other discipline represents a meaningful field of research and scholarship.

I begin with a transparency or Power Point slide depicting, in clusters, some of the disciplines taught in the liberal arts college. 1 cluster, labeled "Natural Sciences," includes biology, chemistry, and physics. Another, labeled "Social Sciences," includes anthropology, sociology, economics, political science, and history. A third cluster, labeled "Humanities," includes art, music, languages, literature, theology, philosophy, and (equally a branch of philosophy) logic & math (with math lying between the humanities and natural sciences). So, after describing this construction and its rationale, I ask rhetorically, "Where does psychology fit in all of this?"

I so get to the next slide or transparency, showing the previous structure but now including PSYCHOLOGY as a big gilt sphere, lying right in the middle, with rays connecting it to each of the disciplines that form a circle effectually it (encounter Figure 1). "Ta-dah," I say, "here we accept information technology — Peter Gray'south Psychocentric Theory of the University. Quite comparable in its brilliance to Copernicus'southward Heliocentric Theory of the Universe. Psychology is the shining sun in the middle of the academy, which illuminates all of the other disciplines."

I say all this with a twinkle in my eye and my tongue planted firmly in my cheek, just then I keep to brand a serious bespeak. The connections betwixt psychology and the other disciplines, illustrated by the sunrays in the drawing, are real connections. Substantive subdisciplines lie on each of those rays, consisting of people both in psychology and in other departments, who often piece of work together. To illustrate this point, I get from ray to ray and say a few words most each of the connections illustrated. Some of these interdisciplinary realms — such every bit biopsychology, psychophysics, social psychology, psycholinguistics, and cultural psychology (connecting psychology and anthropology) — are major subfields of psychology.

It is non surprising that all these connections exist. Psychology is the study of the human listen. The humanities are what man beings everywhere do with their minds, the social sciences study the products of human being minds working in social groups, the natural sciences rely on perceptions and logical processes that emanate from the human being mind, and the listen is a production of a concrete-chemic-biological structure (the brain) that is a subject of natural scientific discipline. So, of grade psychology lies in the center of it all! It would be incommunicable for people from any other section to draw a diagram nearly as elegant as mine that put their bailiwick in the center. As we get through the course, talking near each topic in psychology, I make a point of reiterating the relevant interdisciplinary connections.

Psychology 101 Brings Students up to Engagement on Classic Philosophical Questions

• Does free will exist, or are we robots, controlled deterministically by forces outside of us interacting with mechanisms congenital into us?

• Do our perceptions reflect reality? (Is my shirt really reddish, or exercise I just see it that manner?)

• Where do our ideas and knowledge come from? Exercise they come entirely from our experiences, every bit Locke and other Empiricists believed, or are we born with certain ideas and noesis, as Kant and other Nativists believed?

• Are people basically good, every bit Rousseau believed, or basically evil, equally many Christian philosophers believed?

These are the kinds of questions that philosophers used to contend and that provide much of the core of the history of Western thought. Such questions alive today in psychology. We address these questions with modern prove and logic; we don't just cite the opinions of long-ago philosophers. Indeed, well-nigh everything that we talk about in Psychology 101 can be related meaningfully to one or more than of the classic philosophical questions. In almost cases, the questions equally classically stated are the outset points for our phrasing of more refined questions, and the best answers that we can requite are conditional and circuitous. For example, the question of costless volition might be answered one way or the other depending on only how you define free will. We may be machines, just we are extraordinarily complex determination-making machines. The philosophical question of free will can necktie nicely into a discussion of what we know and don't know nearly the brain's controlling and behavioral control mechanisms. As another example, the Nativist/Empiricist debate lends itself nicely to a give-and-take of the interaction of innate understandings and of sensory experiences in all aspects of mental development, including the development of language and of understanding of the concrete and social worlds.

Psychology 101 Provides Frameworks for Understanding Oneself and Making Life Decisions

Co-ordinate to the Oracle at Delphi, in ancient Greece, the first task of a scholar is to "know thyself." When students are asked what they hope to go out of the general psychology grade, their most mutual answer is that they want to understand people, including themselves, amend, and they desire knowledge that will help them make skillful decisions in their personal and professional lives (see Nelson & Nelson, 2005). We should respect this desire of students. What better reasons could they peradventure have for taking general psychology or, for that matter, for enrolling in the college or university? Nearly all topics in psychology really are relevant to the questions that students bring with them to the course.

Some units of the course are very obviously related to the life problems that interest students. These include the units on human development, social psychology, and personality. The other units are also relevant, just we may take to take special measures to show that. One method that I sometimes use to ensure that my lectures are relevant to students' interests is the following: Earlier we get to a detail topic — before students have read the chapter on that topic and earlier I've lectured on it — I'll ask students to write out honest questions they take on that topic.

For example, before getting to the chapter on retentivity, I'll ask something similar this: "What have you noticed about your own memory or forgetting that has intrigued you? What questions most memory have occurred to you in the course of your life or occur to y'all at present that yous would similar to know the answers to?" Afterward class, I read the students' questions and grouping similar or overlapping questions into categories. Typically, the questions tin can be grouped into somewhere between x and 15 categories. Then, when I lecture on memory (or whatever the topic is), I'll use their questions every bit the structure for everything I say. In addressing their questions, I'll bring in the terms, models, and ideas that the textbook affiliate uses, but I'll organize everything around their questions. I'll focus especially on questions that lots of students asked but besides on questions that seem particularly interesting, even if just ane student asked it.

This method has worked well, in my experience, not just for the topic of memory, merely also for sensory systems (questions about vision, hearing, taste, smell, and hurting), emotions, and motivation. It is important in all cases to veer students away from trying to write academic sounding questions and toward writing, in their own words, the kinds of questions they have really wondered about and might accept discussed with their friends.

Psychology 101 Promotes Critical Thinking

In all my years of reading the teaching goals statements of people applying for jobs or promotion in academic psychology, I have yet to find anyone who did not say that what he or she tries virtually to do is promote disquisitional thinking. If there is anything that we psychologists agree on, it is that disquisitional thinking is of import. And we take good reason for such agreement. Specially at present, with such easy access to data, there is trivial need to commit a lot of information to memory, only lots of need to know how to evaluate information. From a liberal arts perspective, it is hard to imagine any objective more than fundamental than that of improving students' critical thinking. Indeed, one definition of liberal arts education is that it is educational activity that liberates the mind from the bondage of habit and custom.

The good news is that we psychologists are pretty expert at teaching disquisitional thinking. Several research studies have revealed that psychology majors proceeds more in critical thinking over their undergraduate years than exercise majors in other disciplines, including those in the natural sciences and humanities (Lawson, 1999; Lehman & Nisbett, 1990; Williams, Oliver, Allin, Winn, & Booher, 2003). In particular, they become better at evaluating evidence and arguments and at asking the questions that must exist answered to judge whether or not a statement is convincing. In what follows, I'll draw briefly iii categories of means by which we, as teachers of Psychology 101, can and oftentimes do promote the disquisitional thinking of our students.

ane. The explicit instruction of skepticism and of methods for evaluating evidence.

Near of the states elaborate on the value of skepticism and present methods for evaluating evidence in the unit dealing with research methods and statistical reasoning, but, ideally, we also do it at other places throughout the course. Leshowitz, DiCerbo, and Okun (2002) accept described one splendid way to do this. They held recitation sections for which students were asked to read sure articles in the pop media that made psychological claims, and the task within sessions was to debate and critique each commodity. For example, one article was a piece from Time magazine entitled, "The Lasting Wounds of Divorce." It described example histories of young people who had troubled lives later on their parents were divorced, and it quoted a psychologist as concluding the post-obit from her written report of children with divorced parents (which had no comparison group): "Nigh half of children of divorces enter adulthood as worried, under-achieving, cocky-deprecating and sometimes angry young men and women."

If we read this quotation (and the rest of the commodity) uncritically, divorce seems to have terrible effects on children. But if we read it critically, we are left with many questions and no house conclusions. What does it mean to say that "most one-half" were "sometimes angry"? Isn't everyone sometimes aroused? And isn't anybody at least to some degree, at times, "worried" and "cocky-deprecating"? And, statistically, anywhere but in Lake Wobegon, wouldn't we expect one-half of the children (not just "near half") to be nether-achieving, if under-achieving ways below the median in achievement? The questions that students enhance lead quickly to discussions of the need for operational definitions and some kind of comparison group. Students can, from common sense, generate appropriate criticisms, and their learning is far more potent when they practise so than when nosotros do information technology for them.

two. The implicit didactics of critical thinking.

Maybe the most constructive way to teach critical thinking is to model it. Our chore equally lecturers should not be primarily to present information; the textbook can do that best. Instead, we should exist flesh-and-blood examples to our students of people who think critically. Our lectures should be non about facts to memorize, simply about ideas to think nigh, and in our lectures we should implicitly model such thinking. For example, instead of lecturing on Freud, or on Freud's beliefs, or on definitions of all of the defense mechanisms, I choose one of Freud'south most interesting and all the same-relevant ideas and lecture on that, presenting the best understanding we accept today concerning that thought. In the lecture, I describe Freud'due south evidence for this thought, only I would also draw current research that tends to support, refute, or delimit the idea. I define some terms, but the terms are secondary to the ideas. The students become involved in a process of examining evidence for and against an idea, not a process of memorizing names and terms. (I have elaborated on this method of teaching much more fully elsewhere — run into Grayness, 1993, 1997.)

My impression is that we psychologists typically model critical thinking in our classes more fully than do instructors in other disciplines. We do non see our field equally being comprised of indisputable facts or inarguable opinions; rather, we run into information technology every bit a drove of ideas to be supported, refuted, or delimited through evidence and logic. Possibly because of the nature of our subject affair, nosotros are more sensitive than are, say, biologists, to the kinds of errors in reasoning that can pb to false conclusions. We convey that sensitivity implicitly in our manner of didactics.

three. Education psychological content that has to do with critical thinking.

Psychology is, in part, the study of thinking. By didactics students some of psychology'south discoveries almost thinking, and particularly past making students aware of biases affecting thinking, nosotros can help them become better thinkers. If yous become through the textbook that you lot utilize, you tin make a listing of many ideas — from different parts of the book — that have to exercise with thought. The list would include biasing furnishings of social context (e.g. conformity biases), cocky-serving or defensive biases, biasing furnishings of mood, biasing effects of culture, then on. Many of these effects tin exist demonstrated in class, illustrating to the students that they really are susceptible to them. For instance, I sometimes demonstrate the group polarization effect on thought by having students rate the direction and strength of their belief on some consequence that is meaningful to them, such as the suggestion that nosotros should from now on utilise only essay tests, non multiple choice tests, in form. Then I divide the class into groups based on their initial response, putting like-minded people together for further give-and-take. And then, afterward the discussion, I take them rate the strength of their belief again. The effect, every time I've done it, is that opinions become more extreme afterwards the group discussions than they were before.

I also find information technology useful, near the cease of the semester, to present a review lecture devoted to critical thinking, in which I review all of the various ways, discussed earlier in the course, past which our thinking is affected by context, self-serving ends, specific wording, mood, and then on. When students understand these influences, they have the potential to have them into business relationship in their ain thinking and thereby to better their thinking.

Conclusion

If I have convinced you that Psychology 101 is the virtually valuable form that you could possibly teach, I take washed my chore. The class should be taught past the smartest, about broadly knowledgeable, most philosophically inclined, and most defended teachers in the department. And, contrary to the trend everywhere, it should be a two-semester form, not a one-semester course. The grade is too big and too of import to liberal arts educational activity to cram into a single semester. ♦

References and Recommended Readings

Gray, P. (1993). Engaging students' intellects: The immersion approach to disquisitional thinking in psychology pedagogy. Teaching of Psychology, 20, 68-74.

Greyness, P. (1997). Teaching is a scholarly activity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Didactics introductory psychology: theory and exercise (pp. 49-64). Washington, DC: APA Press.

Hall, Due south.S., & Seery, B.50. (2006). Behind the facts: helping students evaluate media reports of psychological research. Pedagogy of Psychology, 33, 101-104.

Lawson, T.J. (1999). Assessing psychological critical thinking as a learning outcome for psychology majors. Teaching of Psychology, 26, 207-209.

Lehman, D.R., & Nisbett, R.Eastward. (1990). A longitudinal study of the effects of undergraduate training on reasoning. Developmental Psychology, 26, 952-960.

Leshowitz, B. DiCerbo, K.E., & Okun, M.A. (2002). Effects of instruction in methodological reasoning on information evaluation. Teaching of Psychology, 29, 5-10.

McCarthy, M.A. (2005). The office of psychology in a liberal arts education: An interview with Diane F. Halpern. Teaching of Psychology, 32, 132-135.

Nelson, D., & Nelson, Chiliad. (2005). The use of principles for organizing the introductory psychology class. Psychology of Learning and Teaching, 4, 95-101.

Penningworth, South.L., Despain, L.H., & Gray, M. J. (2007). A grade designed to ameliorate psychological disquisitional thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 34, 153-157.

Williams, R.L., Oliver, R., Allin, J.Fifty., Winn, B., & Booher, C.Due south. (2003). Psychological critical thinking every bit a course predictor and event variable. Teaching of Psychology, 30, 220-223.

Source: https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/the-value-of-psychology-101-in-liberal-arts-education-a-psychocentric-theory-of-the-university

Postar um comentário for "How Do a Liberal Arts Help a Psychology Degree"